At the beginning of April, Sabrina Boggs interviewed Roman Susan’s Kristin and Nathan Abhalter Smith about their situation with Loyola University and their plans for the future. For more context, you can read their public letter to Loyola and news coverage on their website. This conversation been edited for length and clarity.

What is the current situation?

Kristin: We still have a lease until September 2025. We are the only people in the building with a lease that long. The other commercial tenants have been trying to get their leases extended, but they’ve been getting vague answers. We’ve heard they want to tear the building down.

Nathan: We have 18 months left in the space. Yes, it may go away, but in that time, we want to celebrate what it is, help our neighbors so that they don’t fall through the cracks of development, and advocate to have public-facing cultural spaces for the neighborhood instead of eliminating them.

Kristin: There are reasons why they want to tear this building down. But they should still respect the fact that they’re displacing residents and reducing naturally occurring affordable housing. They should have some responsibility to the whole city to add apartments, not take them away. And if we’re looking at all these public improvements that are happening [around Loyola], why not consider replacing it with another project like this that’s better and functional for everybody? That’s what we want. And it doesn’t even have to be us.

Nathan: If we’re not here, we still want this area to be interesting and engaging, not walled off and institutional. We’re trying to share that with them and see what they might be interested in, or what they’re already thinking. They’re moving at an institutional, sort of glacial pace. They’re thinking about 2050. But it feels a lot different if you live here and you get notice you can’t live here in two months. There’s a pretty big disconnect there, I would say. But there’s still an opportunity for this space to continue being a vibrant space for art.

Kristin: Yeah, as long as they can look beyond the conservative structure of business economy around what it means to be successful. We’ve had a couple of exchanges with them asking about what kind of investments they’re making in arts and culture. There’s a big gap between business economics and arts and culture economics. But there’s a lot of value that people can glean from experiences of culture, and it’s a journey to help everybody respect that what we’re doing is essential.

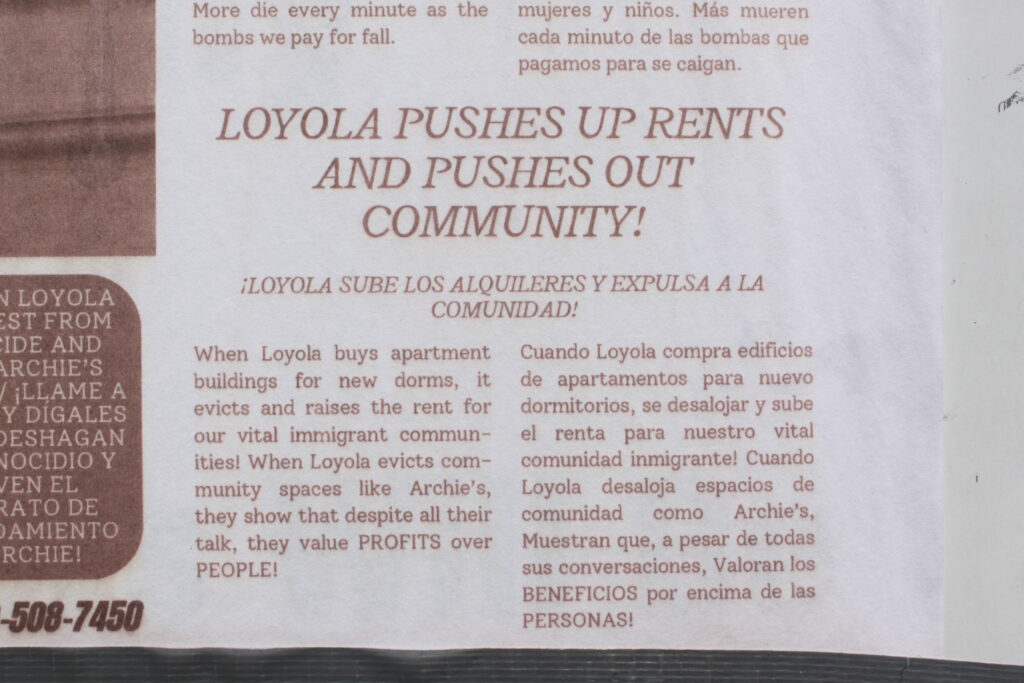

Two dirt lots surrounding the building, demolished years ago by Loyola. And a flyer titled “WHEN WILL LOYOLA STOP?” taped by an unknown passerby on one of Loyola’s signs.

In an article by the Loyola Phoenix, Michael Loftsgaarden said this building is “probably not contributing to the university’s anchor mission.” Do you have any ideas about why that is or if it’s something that can change?

Nathan: It seems like they’re pretty set on tearing this building down. But do they displace everything that’s here, or do they make plans in their development to replace and improve it with more assets? No one can hold them to that, they would just have to decide to do it. There’s no pressure besides their own words.

Kristin: I’m pretty surprised at how callous they sounded and how easily they were willing to say, “We’ve got our own plans, leave us alone.” They seem to tout their mission and their community involvement, and that’s why we want to say, here we are, we’re the community. Let’s have conversations, because we don’t feel like we’re being seen or heard or acknowledged in any of this. And if you are saying that this is your mission, then we’d like to hold you to that.

Nathan: It’s tricky because there’s such a disconnect between intention and the functionality of business. This is a small enough situation where you could approach people individually and be humane before sending non-renewal form letters and stressing people out about their basic needs, but that’s not the business playbook. They’re just doing what you do if you’re trying to clear a building. And that just doesn’t seem in line with their values.

It did seem like some of the pushback was working, because the university later said they would be reaching out to tenants to help with the transition. Did that happen?

Nathan: We did reach out to [Loyola] proactively about it, and they said they would take it under advisement. We have talked to some of the people in the building, and we learned that Loyola is approaching people individually, which equates to them treating people differently.

Kristin: Yeah, it mostly depended on whether or not those people advocated for themselves.

Nathan: One of the things we asked Loyola to consider was offering affordable housing in the apartments they own. They set the rates, so they could definitely do that if they wanted to. Or, allow people to go month to month after their lease is up, as long as we’re here and the building exists. They’re not going to re-rent the apartment so why push people out? […] It puts all these people in a really vulnerable position. They’ve lived here for 10, 15, 20 years. The rent was cheap then and it’s still cheap. It isn’t cheap or even affordable for them anywhere else around here. It really is precarious. And in most situations, the business world just flattens these people. But this is a unique situation in which it’s an institution with a social justice mission. It’s not a huge pool of people, they certainly could accommodate them…

Sabrina: But do they care enough to do that?

Nathan: Yeah, exactly.

Can you elaborate on how the architecture of the space is unique and contributes to the uniqueness of your programming?

Kristin: Because this building is wedge shaped, it’s on a sleepy street, and it doesn’t have large buildings blocking its sunlight, it’s able to be a beacon for the neighborhood. We keep our lights on at night whenever there’s an exhibit so people can see what’s inside, and we’ve heard feedback that people feel safe when they walk by here. This is mostly a pedestrian thoroughfare, so we might never meet many of the people who have an experience with this space. Or they might come in and say, “I’ve been walking by for 5 years. This is great, thank you for doing it.” A lot of our connections to the space have to do with how people move in the world. Because the neighborhood connects to the transit and the lake, and the people who live around the campus aren’t just students, and the students who do live around here share community at Archie’s Cafe… This area is representative of everybody who lives in Rogers Park.

Nathan: I think it’s interesting how the streetscaping and public space interact here. It’s a really small space so it’s manageable for individual artists to completely take it over. It’s also very irregular, so it’s a challenge and opportunity for people to do things they wouldn’t do in an exhibition space. Because it’s always visible from the street, people outside of art circles interact with it, which is definitely my favorite part. It’s great when people travel across the city to go see something, and the Red Line being here facilitates that very well. But it’s really joyful when you’re out in the world and discover art in a public space. Artists respond to the opportunity all of that represents. It lets some people do things they wouldn’t do otherwise, and be less precious about things. It’s really wonderful once you get into the mindset of being responsive to where you are.

This is a unique situation, which is what we’re trying to communicate to Loyola. Respond to it, don’t just go by the book, because you could do better by using what’s already there.

How has this shaped the way you’re thinking about scheduling programming this year and beyond?

Kristin: We want to celebrate our time here and bring through as many artists as possible to help us do that. There’s a project coming up by Madeleine Aguilar that involves building structures and seating, both inside and outside the space. People will be able to activate them with performances and event-based programming. And we have a few exhibits that we’ve been planning for over a year now: sculpture and installation work involving family, grief, and architecture. We’re also trying to engage the community more, as well as tenants in the building. We’ve offered some artist stipends to people because we knew they would be moving out. We’re trying to figure out how to provide the best we can as neighbors.

Nathan: We’re going to have at least one more round of proposals for the final year to see what people want to see. And since we have felt the precarity of this situation for quite a while, we do have four other programs that are not here. People definitely know us most for this space because it’s physically always here, but we’re setting up parallel tracks and doing things elsewhere too.

Kristin: That’s our growth model: instead of trying to find another space, or be bigger, we want to activate public space that already exists. Through the Chicago Park District, we have programming at Berger Park at least once a month. We also have a project called Navigations that’s in and about public space. It’s a commission-based project about storytelling through place.

Nathan: A lot of people naturally have been asking us if we’re going to get another storefront or gallery space. But what we’ve learned is how important and valuable it is to respond to the site you’re in. This program is this room. There’s no bridging it to another space. If we got another space, we would treat it similarly. It would be its own unique thing and it would develop through the ideas of people that come in the door.

Kristin: Right now, we’re trying to drive home the values of this space and we’re not willing to let it go quite yet, or to name what the next thing is. We have all these projects that build off this space, and remind people that their own agency in a space can be activated and celebrated artistically. The idea that this is an anomaly space can be applied to a lot of different ways of thinking about art and public life, and how we move through the world and express ourselves.

We want to be here as long as we possibly can. We’ve always expected that something like this would happen, so when they were trying to get us to leave earlier and buy us out of our lease, we said no. When institutions try to move forward despite what the public wants, we’ll be the unreasonable ones who are like, “Nope. Leave us alone.” As artists with a voice, we can remind people to question what they’re being told.

What can people do to continue supporting you?

Nathan: In this individual circumstance, a lot of the dialogue so far has happened in media, and that seems to be what the institution is responding to. When we first made the letter public, many people who live in the community and have some relationship with Loyola interacted with us and said, “This is not what anyone wants.” There are many times when a larger organization doesn’t represent the values of all the people below it. Just keep having the conversation, and advocate for the values that overlap in the community. Continue to provide opportunities for things to bubble up.

Kristin: Don’t let the story fall away. Keep the attention on the goal, which is to continue to support art, artists, and the people who live in your community. And look out for one another.